While France continues to play a prominent role in the history of international cuisine, since 1975 the world of gastronomy has undergone major upheavals, keeping pace with changes in our lifestyles, eating habits, and ways of thinking. From 1974 up until the 1990s, “la nouvelle cuisine” in France spearheaded a new culinary path, without eschewing the past, championing lighter sauces and preparations.

One man embodied the new face of French cuisine: Paul Bocuse, who inspired a new generation of like-minded chefs such as Alain Chapel, Michel Guérard, Alain Senderens, and Jean and Pierre Troisgros. All owner-chefs, they had one foot in traditional cooking but took the culinary world by storm as they embraced the freedom to innovate and assert their independence.

This led to the birth of a new school of mavericks in the 1980s—Michel Bras, Pierre Gagnaire, Alain Passard, Olivier Roellinger, and Marc Veyrat—who pioneered what became known as cuisine d’auteur (author’s cuisine).

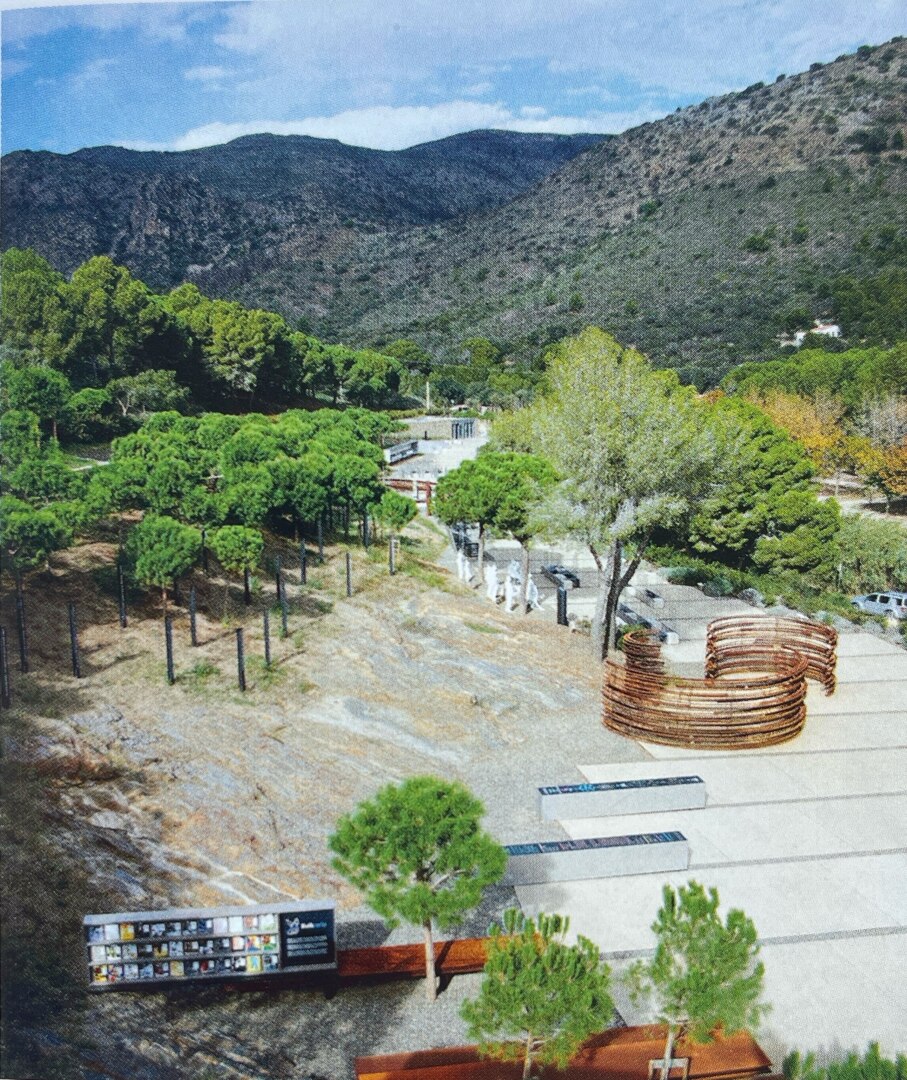

In the late 1980s, Ferran Adrià, then a complete unknown, took over the helm of elBulli, a traditional restaurant overlooking the seaside resort of Rosas. Adrià imposed his avant-garde vision on Catalan traditions, introducing experimental, state-of-the-art techniques: deconstruction, jellies, foams, espumas, spherification… For some twenty years, he turned elBulli into a hotbed of cutting-edge culinary research, drawing foodies from around the world from April to October. Adrià’s influence spread globally, from Heston Blumenthal’s mind-bending innovations at The Fat Duck (Bray) to Grant Achatz’s freewheeling molecular experimentation at Chicago’s Alinea.

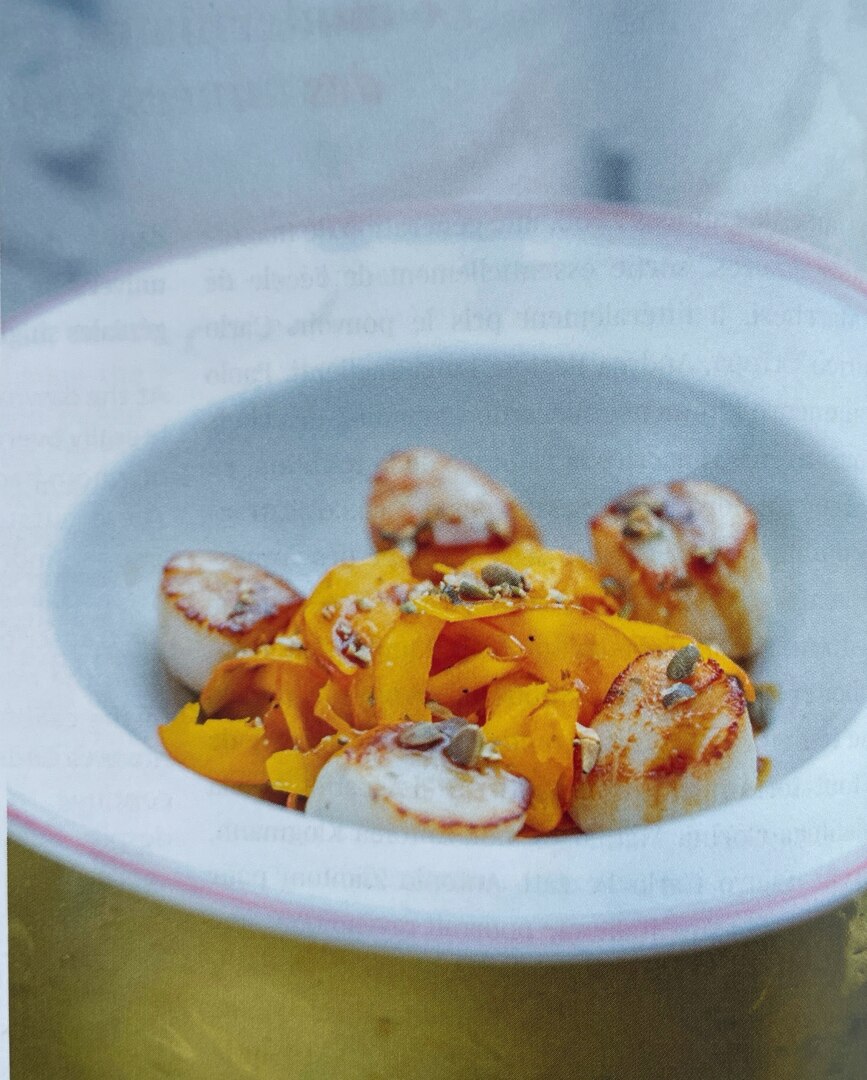

Back in his homeland after training abroad (with Thomas Keller, Adrià, and the Pourcel brothers in Montpellier), Danish-born René Redzepi, only twenty years old, dared to wipe the slate clean. He shone a spotlight on simple, wild ingredients, hand-picked along the coast or foraged in the immense forests of the great North. Exuberant spring and summer vegetables and flowers were followed by harsh winter crops, paired with matching techniques: pickling, canning, and fermenting—whose acidity is to Scandinavians what bitterness is to Mediterranean cooks.

The kitchen of the world had been stripped back, guided by common sense summarized in two words: naturality and seasonality. New Nordic cuisine shed the opulent codes and stuffy rules of European cuisine. It embodied the aspirations of an entire generation to work with the land and soil, motivated by an awareness of the ecological implications of cooking and eating. A “poor man’s” cuisine, perhaps, but resolutely pantheist.

At the dawn of the 2000s, the Italian restaurant scene was overrun by a generation of forty-somethings, many of whom had trained at the school of Gualtiero Marchesi. These outstanding chefs—including Carlo Cracco, Enrico Crippa, Andrea Berton, Luigi Taglienti, Paolo Lopriore, and the acclaimed Riccardo Camanini—demonstrated a flair for reinterpreting Italy’s rich traditions, particularly those from the north. Add to that the virtuoso free spirits like Massimiliano Alajmo, Massimo Bottura, Moreno Cedroni, Fulvio Pierangelini, and Niko Romito, who continue to inspire new generations.

However, despite being home to perhaps the highest concentration of culinary talent in Europe, the Italian restaurant scene seems reluctant to challenge the traditional role of the restaurant in the third millennium or to assert a trailblazing global role for Italy. This is the paradox of Italian cuisine: it is arguably the most popular in the world, yet it has not found the universal key to unlock its collective potential.

Quietly and almost under the radar, a new revolution has been gaining momentum in France: bistronomy. In other words, a return to basics, with more straightforward cooking focused on ingredients, and less likely to follow traditional formulas. A generation of chefs such as Inaki Aizpitarte (Le Chateaubriand), Bertrand Grébaut (Septime), Sven Chartier (Saturne), and Petter Nilsson (La Gazette) are flying the flag of modern French cuisine, rich in contrasts and bold experimentation.

Less animal protein, tasting menus, and natural wine pairings characterize this trend, whose craftsmanship and DIY foundations are underpinned by ethical awareness of the act of cooking. This movement is now known as Naturality.

Whether in Michelin-starred establishments like the Plaza Athénée, where Alain Ducasse and Romain Meder revolutionized fine dining with a plant-based cuisine centered on fish, seeds, and vegetables, or in more modest restaurants like those of Cyril Attrazic in Aubrac or Jérôme Jaegle at Alchémille in Alsace, French cuisine today has made nature its foundation and driving force.

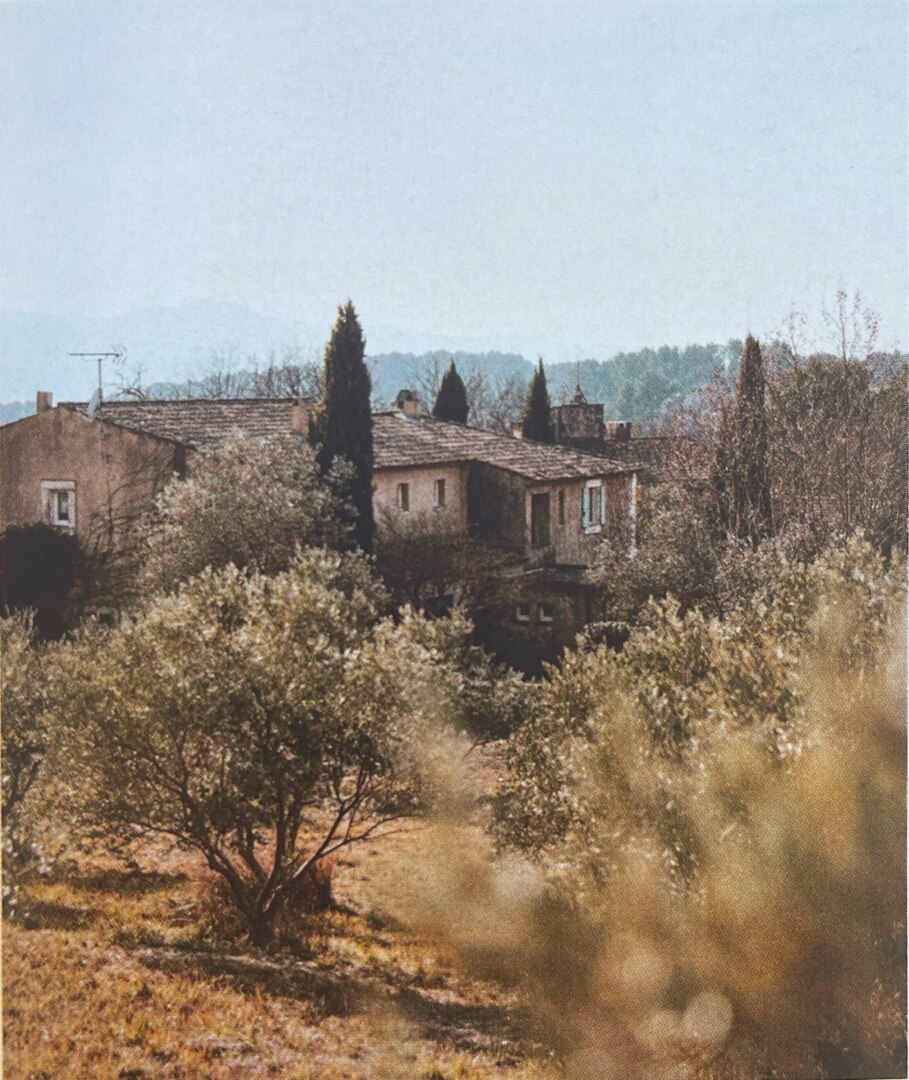

It is “cooking on a human scale, born out of my own experience (with food intolerances, etc.) and my research into healthier and more eco-responsible gastronomy,” to quote Nadia Sammut, the inspired chef of La Fenière in Lourmarin.

The tenets so dear to Alain Ducasse and Romain Meder have influenced vast swathes of today’s fine dining scene. In France and abroad, there is a shared demand for local produce, respect for the seasons and local culture, and a common quest for sustainability.

Source: Teritoria magazine

Fine dining restaurants with Coninvest kitchens